Three blind spots in the passive investing playbook

The hidden cost of zero tracking error, the "rising tide" bias, and the flaws of naive diversification

Every now and then, I open the scientific publication aggregator papers.ssrn.com to hunt for useful new articles. This is as addictive as scrolling Twitter, but much more enlightening. Today I found several papers on passive investing that challenge conventional wisdom.

On the Hidden Costs of Passive Investing

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5327757

Conventional wisdom: index funds that have low tracking error (deviation between benchmark and real performance) are doing a good job.

The paper: zero tracking error means the fund left money on the table.

Market indices such as the S&P 500, FTSE 100, and MSCI benchmarks are dynamic: to maintain accurate representation of their target market segments, securities are periodically added and removed. A large literature documents abnormal return patterns around such index reconstitution events.

One of the reasons for such abnormal patterns is that large public indices announce reconstitutions several days prior to the implementation date, while an estimated ∼ 56% of passive ETFs place much of the trading positions at the closing price of the reconstitution day. These passive investors wait until the exact moment that the index change occurs so that they do not incur tracking error with respect to the benchmark. But, the rest of the market can participate in anticipatory trading of the name that has been announced.

For passive managers, delayed execution of reconstitution trades —especially at the closing auction of the reconstitution day—can result in substantial increase of the implementation costs. Executing trades gradually or in advance (even fractionally) may reduce these costs without materially affecting tracking error which is often the reason for the delayed trading.

So: the whole market knows that passive funds will buy a certain asset on a certain date. Traders buy it in advance and then benefit from rising demand, which means passive ETFs buy the asset when it is expensive, lowering their returns.

The paper mentions this as an opportunity for traders, but I do not think it is feasible for a private investor. This opportunity almost certainly is eaten by high frequency traders with sophisticated algorithms and ultrafast connections to the exchanges. The more practical conclusion: we need to keep this mechanism in mind when we compare ETFs and not assume that lower tracking error is automatically better.

To put it more cynically:

Market indexes are not a perfectly optimized investment mechanism. They have weaknesses. Traders exploit them. Fund managers can turn a blind eye to this so they look perfect and safe with zero tracking error. And the guy who pays both of them is a customer who invests in ETFs.

Negative Cross-Impact from Index Investing

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5449979

Conventional wisdom: index funds increase stock correlation because investors buy and sell assets in bundles.

The paper: there are economic mechanisms which lead to negative comovements; the overall effect of indexing on the correlation may be indefinite.

The negative cross-impact is generated by two economic channels. The first channel is the information-driven substitution effect for assets’ private signals. As the single-asset investors are more informed than index investors, they will trade more aggressively when they observe a higher private signal. Given a fixed supply for the asset, this “crowds out” the demand from the index investors. Thus, index investors will submit a lower demand for the index fund, decreasing the prices of other assets. This channel echos the insights from Haddad et al. (2025), which show that investors with better information have higher demand elasticity.

The second channel is the supply-driven complementarity effect for assets’ supplies. In particular, a higher supply shock of an asset will be cleared by higher demands from both single-asset and index investors. Thus, the index investors will increase their demands for all assets via the index fund, elevating the prices of other assets. Both channels generate negative cross-impacts between asset prices.

The text is pretty dense, but the intuition is simple. Let’s imagine a food court with two types of customers: Specialists and Indexers. Specialists can buy burgers and fries separately; Indexers can buy only the combo meal.

Information-driven substitution effect:

Specialists learn that burgers today are super tasty. Specialists buy only burgers. The price of burgers skyrockets. The price of the combo also jumps, so Indexers go eat sushi sets instead of the expensive combo. Nobody buys fries anymore. The burger joint is forced to make a discount on fries just to break even. The result: burger price up, fries price down.

Supply-driven complementarity effect:

The burger joint has a surplus of meat today and announces a discount on burgers. Combo price is also down, so Indexers go buy it, increasing demand for fries which are scarce. The result: burger price down due to the initial discount, fries price up.

In both cases Indexers are amplifying the natural price competition between assets.

The described mechanics are interesting, but the real blind spot I detected after reading this article is:

A higher ex-ante expected return (e.g., from a higher supply level) benefits the index investors. This is in line with the fast growth of index investing in the bull market after the global financial crisis.

The authors use complex math to explain why index investing becomes more efficient and popular during a bull market. Again, the intuition is easy to grasp: in a rising tide you are well-off if you are staying in the average boat; the risk of jumping between boats in search of the best one brings relatively less reward.

So the narrative “index investing is inherently superior, only a Buffett-like genius can beat the average returns in the long run” might be true in current conditions, but if the market becomes much less bullish, the situation can change dramatically.

We cannot yet estimate how significant the change would be (prediction is futile!) but being aware of this scenario helps us prepare.

International Investing: Diversification and Beyond

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5767162

Conventional wisdom: adding international indices to the S&P500 brings diversification.

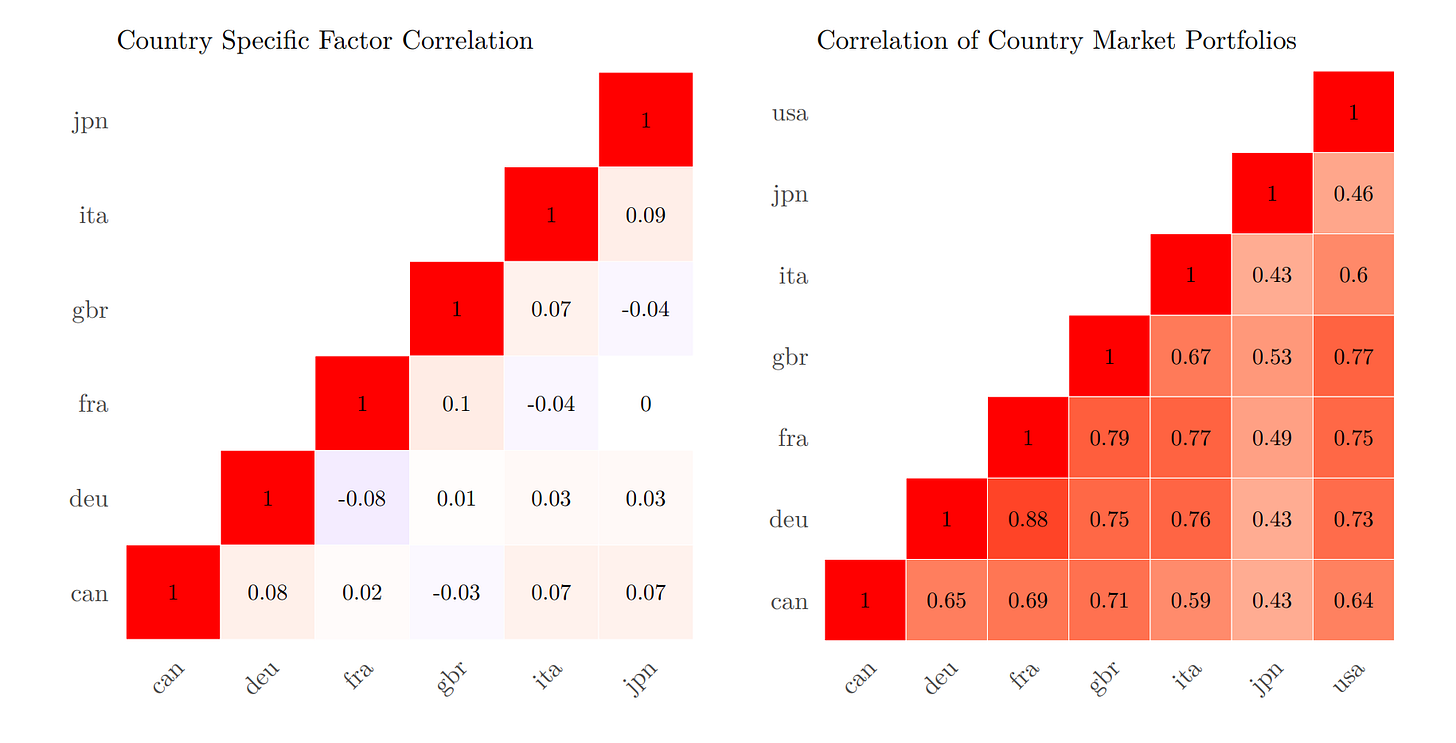

The paper: by buying international indices you are mostly buying exposure to global factors, indices are highly correlated, so diversification benefit is minimal.

Naive international diversification over our sample period yields Sharpe ratios between 0.48 and 0.56. Our approach to exploiting country-specific risk premia yields Sharpe ratios from 1.44 to 2.32.

Sadly, these impressive Sharpe ratios are attributed to a strategy that requires short positions, which makes it inherently more complicated and costly. But the general idea is certainly applicable to long-only portfolios too.

The real diversification comes from tilting the portfolio towards country-specific factors. That sounds simple and logical — when said aloud.

I personally thought that just buying a combination of index ETFs from different regions offers enough diversification. The paper proves this wrong. On the other hand, constructing a portfolio with the right tilts is a significantly more challenging task than just buying an all-world ETF.

That’s the latest catch from the research nets — let’s see what the next haul brings. Stay tuned!

Related article:

This publication is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not investment advice, tax advice, or a recommendation to buy or sell any security. I am not a licensed financial advisor. Investing involves risks, including the possible loss of capital. Always do your own research or consult a professional before making financial decisions.